Sierra Nevada

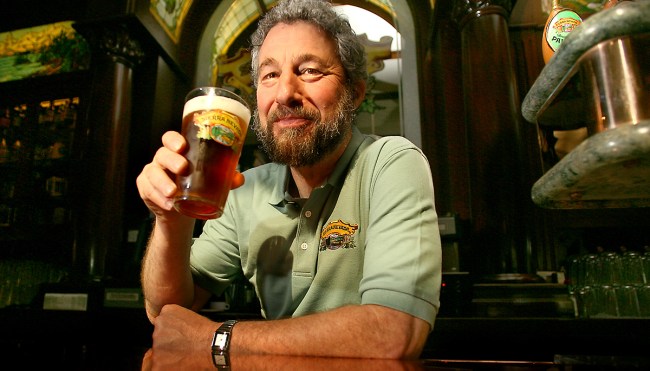

- We chatted with Sierra Nevada founder Ken Grossman about the more than four decades he’s spent in an industry he helped build

- The craft beer legend reflected on the rise of the brewery and shared how it’s managed to remain a major player for more than 40 years

- Read more about beer here

Audio By Carbonatix

As someone who’s been lucky enough to chat with some of the people who were instrumental in transforming the craft beer industry into the behemoth it’s become, I can attest that it’s virtually impossible to talk to a brewer about the people who influenced their journey without hearing the name “Ken Grossman” get mentioned at some point.

After honing his craft as a homebrewer in the 1970s, Grossman decided to turn his hobby into a living when he opened up the legendary Sierra Nevada Brewing Company in Chico, California in 1980. In addition to producing the pale ale that virtually every modern-day IPA owes a debt of gratitude to, Grossman has also inspired countless brewers who followed in his footsteps, including Firestone Walker’s Matt Brynildson and Dogfish Head’s Sam Calagione—the latter of whom credits Sierra Nevada Celebration for opening his eyes to a whole new world.

As a result, I was honored to get the chance to chat with Grossman late last year during a fascinating conversation where he reflected on the incredible path he’s forged over the course of more than 40 years immersed in an American craft beer scene that arguably wouldn’t exist without him.

Can you provide some insight into your personal beer journey and how it led to you starting Sierra Nevada?

As far as my original interest in beer goes, it probably happened when I was a fairly small youngster growing up down the street from a very serious homebrewer, The father of my best buddy from elementary school through college was a very accomplished brewer and winemaker.

He was a metallurgist who worked on rocket engines, but his passion was food, beer, and brewing. He was always boiling up something on the weekends, so as I was growing up, I would constantly be smelling wort and hops. He had rows of five-gallon fermenters bubbling away in the hallway, so I was exposed to the brewing process in some fashion as a youngster.

When I got older, I snuck beer here and there, and then I eventually I started home brewing myself and did that for a couple of years. I moved to Chico in 1972 and continued to homebrew and make a little bit of wine. Then, I opened up a supply store in 1976, where I sold ingredients for making beer and wine as well as teaching brewing classes. At the time, I was studying chemistry in college and was still working in a bicycle shop to help pay the bills.

In 1978, I made the decision to sell the homebrew shop and start a brewer. I had gone on a tour and visited Fritz Maytag at Anchor [in San Francisco] and decided I wanted to be a brewer for my livelihood. I got together with one of my customers, we wrote a business plan, and then started to acquire and build most of the equipment required to build a suitable brewery.

If I’m getting my history right, homebrewing was technically illegal until the federal government passed a law that permitted production for personal consumption in 1978—but you were running a business prior to that point?

Right, it was not technically legal. No.

After the repeal of Prohibition, home winemaking was specifically legalized, but homebrewing really wasn’t part of that bill. However, there were plenty of places where you could buy malt extract and yeast, and homebrewing had been alive and well before then. As far as I know, nobody got arrested for making beer at home.

So Sierra Nevada was officially established in 1979. I hesitate to even use the word “beer scene” based on what I know about the landscape during that time, but what did things look like when you first got up and running?

We eventually made our first batch of beer in November 1980, but it had been a couple of years in the works.

1980 was about the low point in the number of breweries in America. If you look at sort of the first wave of craft brewers, there were six of us nationwide. In California, there was Sierra Nevada, DeBakker, River City, and New Albion. There was also Cartwright in Portland, Oregon, and Boulder Beer in Colorado. There were also some older legacy breweries like Anchor that had been revitalized, but that was really it.

Craft beer has always been an incredibly collaborative industry. How did you communicate back then and how was information shared and spread in the early days?

Ken: From a technical standpoint, we were fortunate that UC Davis was right down the road. I spent quite a bit of time at their brewing library and talking to Michael Lewis—who was the brewing professor at the time—and talking to the program’s grad students.

A lot of brewers just got together because we all needed the help. I knew the founders of Boulder Brewing Company—they came out to California and spent the night a few times— and we tried to figure out how to put a brewery together, but the networking was few and far between compared to how it is today.

I eventually got involved with the Brewers Association of America, which had been founded in World War II to protect the interests of small brewers who couldn’t get bottle caps at the time; steel and tin were rationed because it was being used in the war effort as the steel was being rationed. Big brewers were still able to get them, but the little ones struggled, so they all banded together and formed the BAA.

I went to my first convention in the early 1980s, where I basically got to meet people from all of the small breweries in America (which was still really just a handful).

To touch back on your original business plan, what was your initial vision for Sierra Nevada?

At the start, we did three beers: a pale ale, a porter, and a stout. We were partially inspired by the breweries that were around at the turn of the century—we had these old brewing books where they’d advertise “ales, porters, and stouts”—so we figured we’d have that as our core lineup.

We did think that the pale ale was gonna be our flagship, but we wanted to have a portfolio. As a homebrewer, I brewed a lot of different styles of beers, lagers and ales, dry hop beers, and I was trying to, I guess, take some of my homebrewing chops into the commercial side and brew the styles I liked as well.

The largest brewers at the time weren’t exactly pushing the envelope on the style front, so I can imagine there were also some challenges when it came to attracting consumers. What was your initial customer base and how did you have to grapple with the typical drinker’s palate?

The biggest way to spread the word was by going to beer festivals and putting on tastings. The consumer didn’t really know much about beer. Today, a craft beer consumer may know more about hops and malt than all of us did back in the 1970s. There’s just so much knowledge today that’s available on the internet. Back then you really had to work hard at educating yourself on being a brewer and brewing and brewing ingredients and suppliers.

There were a couple of brewing industry publications that published annual lists of all the breweries in the country along with a tiny blurb about their CEO, how many barrels they were producing, that kind of stuff; if I wanted to talk to the brewmaster at some smaller brewery in Wisconsin, I had his contact information and phone number, you can just call him up.

The education aspect was a huge hurdle. It wasn’t just the customer. If you wanted to get into a new market, you had to educate the wholesaler, too. They were used to dealing with tractor-trailers filled with light lager all day; they knew a ton about how to load and unload cases on a truck, but they weren’t there to educate the consumer or the retailer about the products that they were distributing.

So, we had to educate them, the sales reps, and then the people who worked at liquors stores, bars, and restaurants about beer. Since none of us had real marketing budgets, it was really one of those things where you had to go sell the beer for the wholesaler and then he would hopefully deliver it.

Virtually none of the breweries that started around the same time still exist today? Why do you think Sierra Nevada is still going strong more than four decades after you made your first beer?

Well, we were determined not to fail. We had invested every penny we had. I had no backup plan. I had to make it work.

There was also our focus on quality and consistency. We dumped a lot of batches early on until we were able to duplicate them every single time. We didn’t go to market until we really had a product that we could consistently deliver; a number of our peers had quality issues from both contamination and consistency that we didn’t have to deal with.

Everybody else really struggled. We were all undercapitalized. We knew how to brew beer, but we weren’t very knowledgeable about the commercial brewing industry. You had to learn quickly and not make too many fatal mistakes.

We were also fairly patient. Some of our peers took on a lot of debt and were forced to close when things didn’t pan out. We really only expanded when we knew we could sell the beer. We didn’t get over our skis from a financial leverage position. When you combine that with the quality, focus, and distinctiveness of our beer probably, it helped us to survive and grow.

I’ve talked to so many other brewers who’ve become legends in their own right who cite you as one of their biggest influences. What has it been like to not only be one of the founders of a movement but someone who was instrumental in paving the way for others who became your de facto competitors?

I’m proud to have been part of that and played a role in that. I have to give some credit to Fritz at Anchor, because he was really the first person who proved American beer could sit at the table with the best beers in the world,

Following in his footsteps and then being part of that wave that continued to evolve and influence consumers—and then brewers—is something that was great to be a part of.

The craft beer industry has experienced plenty of highs and lows over the past four decades and you’ve been there to witness them all. There are a lot of people who’ve speculated the explosion we’ve seen over the past ten years or so has created a potential “bubble” and I’d love to hear what you have to say on that particular matter.

We’re in a very unique time; I’d actually say these are the craziest times I’ve ever experienced in our industry. Our biggest competitors today though are all multi-national corporations, which makes the competitive side of the business challenging for any independent small brewer.

You’re dealing with very well-funded global entities that could put a lot of market pressure on their wholesalers and on the retailers. They’re also bringing big portfolios of not only beer but spirits as well as the alternative type kind of beverages. So, it’s a different playing field today than we’ve ever had.

The pandemic certainly didn’t help a lot of the small brewers who were dependent on that direct connection with their consumers. The taproom models have really been challenged. The brewers who didn’t pivot to packaged products have really had a difficult time. Today we’re faced with a lot of supply chain challenges both from a cost standpoint, and availability. Equipment is difficult to get. Aluminum cans are very difficult to get and getting expensive. The malt situation—barley growing in the drought conditions we’ve had across much of North America has been challenging on the barley and oats and wheat supply for brewing with.

It’s an interesting time to be a brewer; I don’t think there’s necessarily a bubble, but it’s just a very competitive marketplace today.

Portions of this conversation were edited for clarity.